Bullet castings for target shooters

by John Robinson

Bullet casting

Bullet casting, like reloading, is not necessary complicated and does

not need a lot of expensive equipment. However, badly cast bullets will

significantly affect accuracy and there are a number of fundamental

rules that have to be observed by those wanting to cast target-grade

pistol projectiles.

Getting the lead right

Getting the lead right

One of the most important factors in casting good target pistol

projectiles is in getting the correct lead alloy for the application.

Pure lead is a poor bullet alloy and is only suitable for use in black powder arms. It is too soft for use in smokeless powder loads and also does not cast as well as the lead alloys that have been developed for bullet casting.

In some older publications on bullet casting, a 90 per cent lead/10 per cent tin alloy is sometimes recommended. Those with plentiful supplies of solder may be tempted to go down this track. Most soft solders are 50:50 lead/tin and are relatively easy to mix with pure lead.

Again, this alloy is okay for black powder loads but has the potential to cause leading problems with smokeless powder firearms. Tin has an affinity for sticking to steel, which is why it is used in solder in the first place, and is a very expensive metal and should not be wasted needlessly by overdosing bullet alloys.

Lead alloys consist of additions of antimony and tin. The antimony provides the hardness and the tin assists the fluidity of the alloy and improves the dispersion of the antimony in the alloy.

On a hardness scale of 1:10, pure lead is one and linotype metal, which is about 84 per cent lead, 12 per cent antimony and four per cent tin, is ten. If you hit a piece of linotype metal with a hammer it will most likely shatter rather than flatten.

The presence of antimony provides a couple of other advantages. One is that it lowers the melting point of the lead alloy and improves the fluidity of the lead. This allows it to precisely fill the form of the bullet mould.

The other is that it counteracts the shrinkage that is normally present

when molten metals cool and thus the bullet’s finished size is very

close to that of the mould in which it is cast.

The other is that it counteracts the shrinkage that is normally present

when molten metals cool and thus the bullet’s finished size is very

close to that of the mould in which it is cast.

For most target pistol applications, linotype alloy is unnecessarily hard and a waste of valuable ingredients. Also, with the change in printing technology, linotype technology has almost disappeared, so getting supplies of the alloy is now difficult.

The best source of bullet casting metal is wheel weight (the clip-on and not the stick-on type). These contain three per cent antimony and about 0.25 per cent tin.

This level of hardness can handle velocities up to 1200fps without problems in most handguns and it is only if rifle-type loads, as used in silhouette pistols, are used that harder bullets may be required.

One good thing about these wheel weight alloys is that they are heat

treatable to significantly increase their hardness. Properly

heat-treated bullets made from three per cent antimony alloy have the

potential to be as hard as linotype.

One good thing about these wheel weight alloys is that they are heat

treatable to significantly increase their hardness. Properly

heat-treated bullets made from three per cent antimony alloy have the

potential to be as hard as linotype.

Heat treatment can be done in a kitchen oven by racking the bullets in a single layer in a wire tray on aluminium foil. To establish the correct heat-treating setting for the particular oven, the oven should be set on 220°C and slowly increased in small steps until there are signs of the bullets slumping or wrinkling on the surface. This can be checked with a small number of bullets.

Once the melting temperature has been established, the oven can then be backed off until a batch of bullets can be left in for a prolonged period without any visible changes occurring.

Each batch can then be placed in a pre-heated oven for at least 30 minutes and then taken out and dumped in a bucket of cold water instantly. This hardening phenomenon is called precipitation hardening and any cold working of the bullet after hardening will cause the alloy to start to soften. For this reason the bullets should be sized before heat-treating.

Bullet design

Bullet design

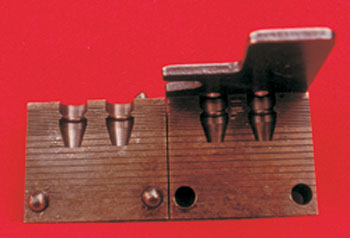

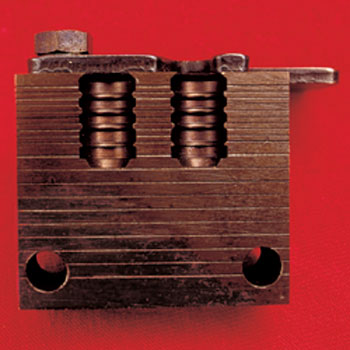

Cast bullet design is important for two reasons. One is that the bullet

form needs to be selected for its intended application. For precision

paper punching, a wad-cutter design works well, while action matches

requiring the use of speed loaders are best suited to projectiles

without sharp edges and shoulders.

The other reason is that some bullet forms are harder or slower to cast than others. A bullet mould with sharp corners and multiple lube grooves tends to be more difficult to remove from the mould after casting. This can be really irritating, as it is necessary to bump the mould harder to get them to fall free or, in some cases, pull them out of the cavity with pliers.

Sticky bullets dramatically slow down casting and for that reason multi-grooved wad-cutter designs should be avoided, when possible, if productivity is the aim.

Some good, easy casting designs include double-ended bevelled edge

wad-cutters with a single central groove and most round-nose or

cone-point designs. One of my favourites is RCBS’s 09-124-CN, which is

a 124-grain cone point .38/9mm/.357 projectile that has shot with

wad-cutter accuracy in every revolver I have ever tried it in.

Some good, easy casting designs include double-ended bevelled edge

wad-cutters with a single central groove and most round-nose or

cone-point designs. One of my favourites is RCBS’s 09-124-CN, which is

a 124-grain cone point .38/9mm/.357 projectile that has shot with

wad-cutter accuracy in every revolver I have ever tried it in.

Good bullet mounds have subtle design features on the angles and corners of the mould cavities that facilitate their easy exit from the mould. Saeco moulds are particularly good in this respect.

Bullets with plenty of parallel bearing area will generally shoot better than those that are short on bearing area, particularly as the load pressures increase.

Bullet melting

Bullet alloy can either be melted in a gas-fired steel pot or in an

electric pot. The electric pots are more convenient as they have a

thermostat control, but they require a supply of smaller lead alloy

ingots that are clean. The bottom-pour electric pots are easy to use

and as long as the pot valve does not leak, they provide reliable

service.

Gas-fired pots are more robust and can be used for doing the rough stuff, such as melting the steel clips out of wheel weights and can tolerate a lot more thermal shock than most electric pots.

My preference is for a gas-fired pot, as it is easy to dross the alloy and quickly return cut sprues (the overflow lead off the top of the mould) to the pot. A dipper is needed with a gas-fired pot to ladle the lead out and pour it into the mould and I have used an RCBS aluminium dipper for many years without any problems.

The main trick with melting bullet metal is to get the temperature

right. This means that the alloy is hot enough to flow freely but not

too hot as to take a long time to solidify in the mould. A temperature

of about 420°C should be about right for most bullet alloys.

The main trick with melting bullet metal is to get the temperature

right. This means that the alloy is hot enough to flow freely but not

too hot as to take a long time to solidify in the mould. A temperature

of about 420°C should be about right for most bullet alloys.

With time, a mushy scum may develop on the surface of the molten alloy. This is called dross and is an oxidised mixture of some of the alloying ingredients. Some casters skim it out of the pot and throw it away. This is a waste of good alloying elements.

The best way to deal with this is to cut a 12mm piece of a paraffin candle and, in a well-ventilated area, drop the lump of paraffin on the top of the molten metal. It will start to smoke. The fume is combustible and if it does not ignite spontaneously, it should be lit with a match, which will reduce the fume. Stirring the metal vigorously while the paraffin burns will create a reaction that de-oxidises the mushy material, returning the alloys into solution in the lead and leaving a dry, powdery residue on the surface, which can then be skimmed off.

Bullet casting

Rule number one is to get the bullet moulds up to casting temperature,

which is more than 300°C. This is where gas firing comes in handy,

as

residual heat from the burner can be used to preheat the mould.

Otherwise, it is necessary to cast enough bullets to get the mould up

to temperature. This is easier with heavy bullets but can be

time-consuming with little .32s.

Cold moulds produce defective bullets with wrinkles and rounded corners instead of sharp corners. Even slightly cold mounds can result in the alloy not filling the cavity completely.

A good measure of correct alloy and mould temperature is the time taken for the sprue to set on top of the mould. This

overflow section of alloy should freeze in two to five seconds of

pouring. If it freezes immediately, the mould is too cold.

A good measure of correct alloy and mould temperature is the time taken for the sprue to set on top of the mould. This

overflow section of alloy should freeze in two to five seconds of

pouring. If it freezes immediately, the mould is too cold.

Overheating can damage the alloy and give the bullets a frosted appearance. The alloy may become highly fluid at high temperatures and will flow into the tiny air vent grooves in the face of the mould block. The bullets will emerge with ‘whiskers’ as a result. At high temperatures, the sprue will take a long time to set and may not cut off cleanly, slowing down production and producing defective bullets.

Lubricating and sizing

The importance of lube sizing is often overlooked. It has been established that the closer the as-cast size of the

bullet is to the bore diameter of the firearm, the better the accuracy.

Heavy sizing of cast bullets to get them to a specific bore diameter is

detrimental to accuracy and sizing of no more than 0.001" to 0.002" is

recommended.

Sizing tools from RCBS, Saeco, Lyman and others have specific sizing-die sizes available above and below standard, usually in 0.001" increments.

Most commercial lubricants work well and formulations are available to suit various applications. For moderate velocities, it is possible to make your own lube using a mixture of white petroleum jelly and beeswax in about 50:50 proportions. The proportions can be varied depending on the seasons as more beeswax makes the lube stiffer and less makes it runnier. I have had good results with this mixture with most mid-range loads travelling at less than 1000fps.

Gas checks

Plain-base bullets can show signs of distress as velocities are

increased as the heat of combustion and the pressures applied to the

bullet base can exceed the ability of the alloy to tolerate these

stresses.

Bullet designs for these hotter loads require a gas check to be fitted.

This copper cup is crimped onto the stepped heel of the bullet during

the sizing process and all the cast bullet suppliers can supply gas

checks to suit their particular projectiles.

Bullet designs for these hotter loads require a gas check to be fitted.

This copper cup is crimped onto the stepped heel of the bullet during

the sizing process and all the cast bullet suppliers can supply gas

checks to suit their particular projectiles.

Gas checks will work if the bullet alloy is too soft in the first place. The acceleration forces are considerable and if the lead alloy is too soft, the bullet will upset inside the barrel and deform. Bullets with long points will actually get shorter under these circumstances and accuracy will suffer.

Storage

I have always stacked my cast bullets in cardboard boxes, base down on

cardboard spacers. This prevents the base of the bullet becoming

contaminated with bullet lube.

Greasy, petroleum-based products can contaminate smokeless powder and with small amounts of powder used in most target loads, a percentage of contamination that de-activates the powder can cause accuracy problems.

Heat-treated bullets should be used within a reasonable time of casting, as throughout time they will gradually soften; however, they should keep for a year or so without problems.

While there is nothing like practical experience in casting good, target bullets, some worthwhile publications on the subject include RCBS Cast Bullet Manual and Lyman’s Cast Bullet Handbook, which should be available through major gun shops or via gun-book specialists on the Internet.

Both these books contain illustrations of each company’s bullet designs, handloading information for cast bullets and considerable technical information on lead alloys and their characteristics, as well as bullet casting techniques and fundamentals.